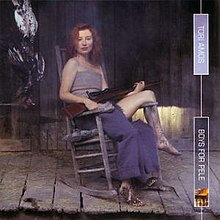

Twenty years ago, Tori Amos released Boys for Pele, a powerful album named after the Hawaiian goddess of volcanoes. I’d only become aware of Tori earlier in the year, around the same time I’d started corresponding with Neil Gaiman. It was 1996, back when you’d go to the record store to buy music. All they had in stock at the store I went to was this new album. Since I’d never heard her music before, Pele was my first exposure to her work.

Twenty years ago, Tori Amos released Boys for Pele, a powerful album named after the Hawaiian goddess of volcanoes. I’d only become aware of Tori earlier in the year, around the same time I’d started corresponding with Neil Gaiman. It was 1996, back when you’d go to the record store to buy music. All they had in stock at the store I went to was this new album. Since I’d never heard her music before, Pele was my first exposure to her work.

As I listened to Pele in my tiny in-law apartment in San Francisco, I was blown away by both the music and her passionate, dreamlike lyrics. Not only had I never heard anything like it before, I was in the middle of a divorce and some huge life changes (to put it mildly) that had cost me many friends. So, Pele spoke to me like nothing else.

On July 12, 1996, I went to see her perform at the Paramount Theater in Oakland. “Tori Stori” is what I wrote to Neil that night after I saw her. It mimics the style of the piece he’d written for Tori in the show’s program.

In honor of the 20th anniversary release of Boys for Pele, here’s the piece I sent him.

*****

“Tori Stori”

There was a girl.

She was dressed in black and leather, for that was all she knew how to wear well, and she came to see the red-headed woman play. And sing.

The girl arrived quietly. Alone. For she didn’t know anyone who liked the red-headed woman, except a man who lived half-way across the country.

She entered the old art deco theater – the “moderne” architecture – and sat, nicely setting aside the memories of yesterday that the building pulled from her. Not yesterday as the day before, but yesterday a hundred years ago. She thought, “I’m going to enjoy today, for it’s what I’ve got now.” And she did.

Others arrived. Younger ones. They sat behind her and talked.

“Aren’t Neil and Tori dating?” asked a young girl.

“Who’s Neil?” asked a boy.

“You know, Neil Gaiman?” another young girl responded authoritatively, yet she sounded as if every statement were a question. “He’s, like, this writer? He, like, writes comic books? BUT,” she hastily added, “he’s very, very talented.”

The girl in black laughed. Quietly.

Then after other, less intelligible discussions, one of the young girls began reading out loud from the programme. After only a few words, the girl in black knew the man who lived half-way across the country wrote that. (“I can name that author in three words, Bob.”)

She got up and bought a programme. And read it.

The lights went down. People cheered, screamed, clapped. “Billy Ray was a preacher’s son. When his daddy would visit, he’d come along…”

Out came the red-headed woman onto the stage. She was small. She sat at the piano and started to play. And play. And sing. My, could she sing. And she moved. Up. Down. Stomping her foot. She reminded the girl in black of a billy goat, bucking and stomping, moving her head up and down. But playfully. Passionately. A Leo. Definitely a Leo.

The red-headed woman keened. Not just about horses, and leather, and Charlie Brown, but about lost loves, a mirror-cracked childhood, and God…

The girl in black cried. And she did not stop crying.

The incredibly lovely, melancholy swells from the Bosendorfer washed away the numbness of pain and stress in the girl’s heart and opened a river in her flesh. For the first time, she didn’t care if anyone saw her cry, like she did sometimes watching movies with boys. She rested her head back. And wept.

Much, much too soon, it ended. The red-headed woman finally left the stage (it was the fourth time she’d left the stage). The lights went up. Everyone was standing, clapping. Including the girl. Especially the girl.

Then the girl left. As quietly as she came. She went home.

And she wrote this to the man who lived half-way across the country.

7/13/96